Do you need a free tool to help you in writing your research proposal?

Try AnswerThis – www.answerthis.io

It can help you to write, refine, and review your research proposal.

Writing a research proposal is one of the most important steps in your academic journey.

It is not just a formality.

It is a test of clarity, thinking, and planning.

A research proposal answers one simple question.

Can you clearly explain what you want to study and how you plan to do it?

Many students struggle because they do not follow a clear structure.

They jump between ideas.

They overcomplicate language.

They lose focus.

This guide explains a simple and proven research proposal outline, exactly following the structure shown in the infographic.

If you master this structure, writing proposals becomes much easier.

1. Title and Abstract

The title is the gateway to your proposal.

It should be short, specific, and informative.

A strong title tells the reader what the study is about without guessing.

Avoid vague words like “A study of” or “An analysis of”.

Be direct.

For example, instead of writing “A Study on Student Learning”, write something more focused, such as “The Impact of Online Learning Tools on Undergraduate Student Performance”.

The abstract comes next.

This is a 200-word summary of your entire proposal.

In one short paragraph, you explain the topic, the research problem, the methodology, and the expected contribution.

Many universities reject proposals simply because the abstract is unclear.

A helpful guide on writing abstracts can be found here:

https://www.springer.com

Although the abstract appears first, it is best written last.

That way, it accurately reflects your proposal.

2. Introduction

The introduction explains what problem you are addressing and why it matters.

Start with context.

What is happening in this research area?

Why is this topic important today?

Then narrow down to the specific issue your study focuses on.

This is where you clearly state the research problem.

After the problem, introduce your research question.

It should be clear, focused, and answerable.

Avoid adding methods or results here.

This section is about framing the problem, not solving it.

A well-written introduction makes the reader want to continue reading.

Do you need an all-in-one tool for researchers?

Try SciSpace: www.scispace.com

It offers many FREE features ranging from literature review to paper writing.

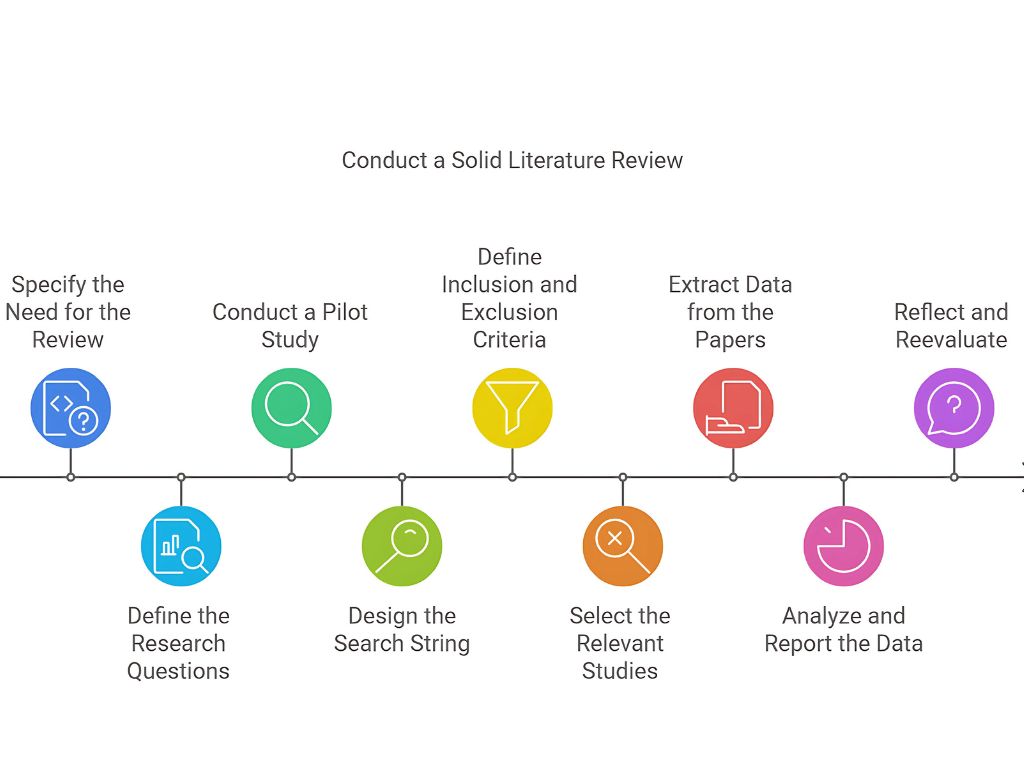

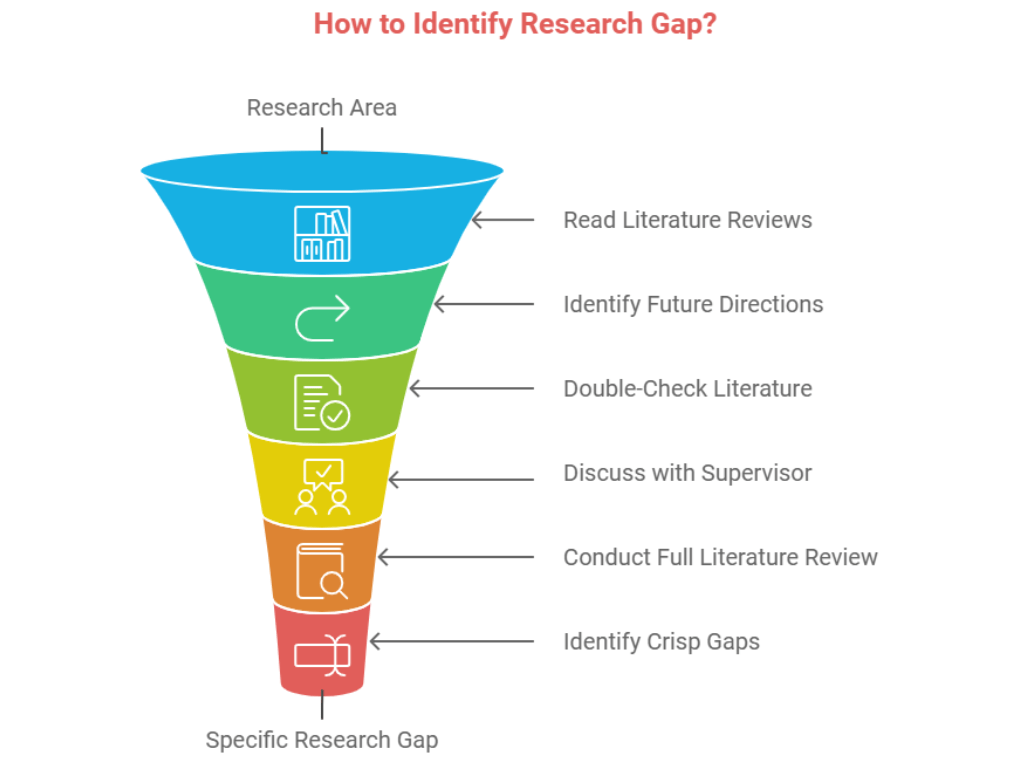

3. Literature Review

The literature review shows that you understand existing research.

This section discusses key findings from 10–15 relevant studies.

Not everything ever published.

Only the most important work related to your topic.

Instead of listing papers one by one, group studies by themes.

Discuss what researchers agree on.

Highlight where results differ.

Most importantly, identify what is missing.

That missing part becomes your research gap.

A useful starting point for literature searches is Google Scholar:

https://scholar.google.com

You can also use databases like Scopus or Web of Science if you have access.

Table: Organizing Literature by Theme

| Theme | Key Authors | Main Findings | Research Gap |

| Online Learning | Smith (2021), Lee (2022) | Improves flexibility | Limited focus on performance |

| Student Engagement | Khan (2020) | Higher motivation | Lack of long-term studies |

Table 1: Sample structure for organizing literature review themes.

Tables like this help readers quickly understand how your review is structured.

4. Research Methodology

The methodology explains how you will conduct the study.

This section should be clear and realistic.

First, describe your research approach.

Is it qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods?

Next, explain how you will collect data.

Surveys.

Interviews.

Experiments.

Observations.

Then describe your participants.

Who are they?

How many?

How will they be selected?

Finally, explain how you will analyze the data.

Statistical tests.

Thematic analysis.

Software tools such as SPSS, R, or NVivo.

A simple methodology explanation is often more convincing than a complex one.

For methodology examples, see:

https://research-methodology.net

5. Timeline

A strong proposal includes a realistic timeline.

This section shows that you understand how long research actually takes.

Break the project into stages.

Literature review.

Data collection.

Data analysis.

Writing.

Assign time to each stage.

Weeks or months.

Avoid overly ambitious schedules.

Supervisors notice unrealistic timelines immediately.

Example Figure: Research Timeline

Figure 1: Sample research timeline showing project phases across months.

(Example: Month 1–2 literature review, Month 3 data collection, Month 4 analysis, Month 5 writing.)

Figures like timelines help readers quickly visualize your research plan.

6. Ethical Considerations

Ethics are not optional in research.

This section explains how you will ensure ethical conduct.

You should mention informed consent, confidentiality, and data protection.

If participants are involved, explain how their rights will be protected.

If your study involves sensitive data, address that clearly.

Most universities require ethical approval before data collection.

You should show awareness of this process.

A helpful overview of research ethics is available here:

https://www.ukri.org/manage-your-award/good-research-resource-hub/

7. Resource Requirements

Every research project needs resources.

This section explains what you need to complete the study.

It may include software, equipment, access to databases, or funding.

If a budget is required, provide an estimate.

If no funding is needed, clearly state that.

This section reassures supervisors that your project is feasible.

8. References

The final section is the reference list.

Include 15–20 high-quality references.

Peer-reviewed journals.

Academic books.

Credible reports.

Every reference must be cited in the text.

Formatting should follow the required style, such as APA or Harvard.

Poor referencing can weaken an otherwise strong proposal.

A referencing guide can be found here:

https://www.citethemrightonline.com

Final Thoughts

A research proposal does not need complex language.

It needs clarity.

If your idea is clear, your structure is logical, and your plan is realistic, your proposal will stand out.

Follow this outline.

Write one section at a time.

Do not rush.

A good proposal is not about impressing others.

It is about showing that you are ready to do research.